Source: www.slate.com

The first innovators of abstract art have long been thought to be artists such as Mondrian, Kandinsky and Malevich.

Although not widely known until well into the twenty-first century, Swedish artist Hilma af Klint is now also hailed as one of the first pioneers of abstract art. In fact, she is considered by some to be the mother of abstraction, as she began painting abstractly as early as 1906, several years before these other artists.

Spring landscape– Scene from the Bay of Lomma (1892)Hilma was born in 1862 in Stockholm to a family of naval officers. She belonged to the first generation of European women artists who studied at the art academies, beginning her training in 1880 at the Technical School in Stockholm, then attending the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm from 1882-1887, where she graduated with honours. In the late 1880’s, she was awarded a studio in the heart of Stockholm’s art scene, and became a respected figurative and landscape painter.

Spring landscape– Scene from the Bay of Lomma (1892)Hilma was born in 1862 in Stockholm to a family of naval officers. She belonged to the first generation of European women artists who studied at the art academies, beginning her training in 1880 at the Technical School in Stockholm, then attending the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm from 1882-1887, where she graduated with honours. In the late 1880’s, she was awarded a studio in the heart of Stockholm’s art scene, and became a respected figurative and landscape painter.

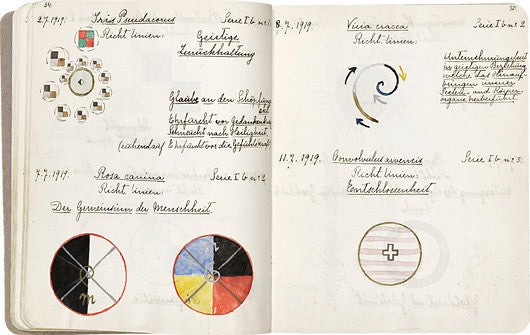

Although she showed and made a succesful living from her representational work, Hilma never showed her non-objective paintings during her lifetime. In fact, she specified in her will that her abstract work was not to be shown until 20 years after her death, as she felt that the world wasn’t ready for this type of art. Working mainly in secret, she left behind around 1300 non-figurative paintings that had never been shown to outsiders, and more than 125 notebooks and sketchbooks. It wasn’t until 1986 that some of this work saw the light of day, when a few pieces were included in a group show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

|

|

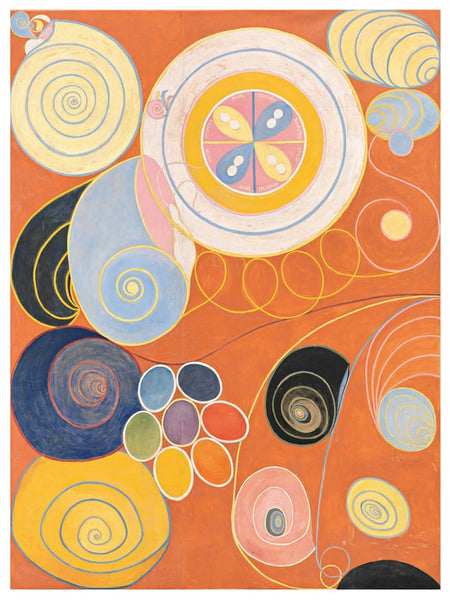

Image A: Group IV, The Ten Largest, No. 7 Adulthood (1907)

Image B: Group IV, The Ten Largest, No 4. Youth (1907)

INFLUENCES

a) Spiritualism. The biggest influence on Hilma’s work was her interest in spiritualism - the belief in communicating with unseen spirits in order to gain insight into the nature of existence and the divine. The movement began in the 1830’s, and became widely popular at the turn of the century, especially among intellectuals and the avant garde. Communication with spirits was attempted through seances, which were set up like scientific experiments in an attempt to prove the existence of a metaphysical world through scientific means. They also employed automatic writing, automatic drawing and ouija boards.

Hilma’s interest in spiritualism began in 1879, at the age of 17, and increased the following year after the death of her sister. In 1896, Hilma formed a group with four other women called “ The Five,” who met regularly to conduct seances, and she soon became the medium of the group. The Five claimed to have connected with spirits who wanted to convey messages to humanity via pictures- these “ High Masters” were named Gregor, Clemens, Amaliel, Amanda, Esther and Georg. During a seance in 1904, Hilma said Amaliel commissioned the group to do a large project, but only Hilma accepted. From 1906 to 1915, she fulfilled the commision by creating The Paintings for the Temple, a series of 193 paintings.

Image A: Group IV, The Ten Largest, No. 1 Childhood (1907)

Image B: Group IV, The Ten Largest, No 3, Youth (1907)

Image C: Group IV The Ten Largest, No. 6, Adulthood (1907)

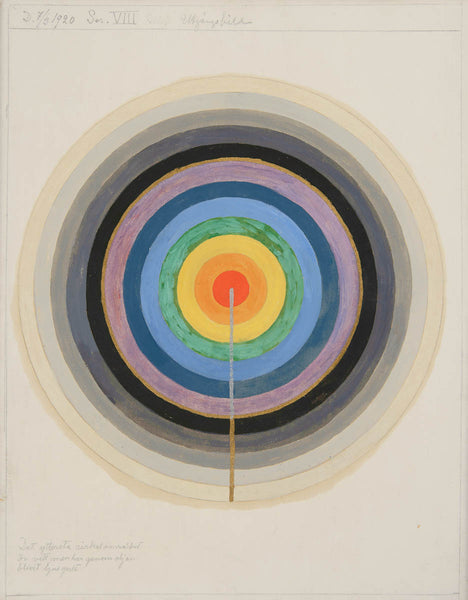

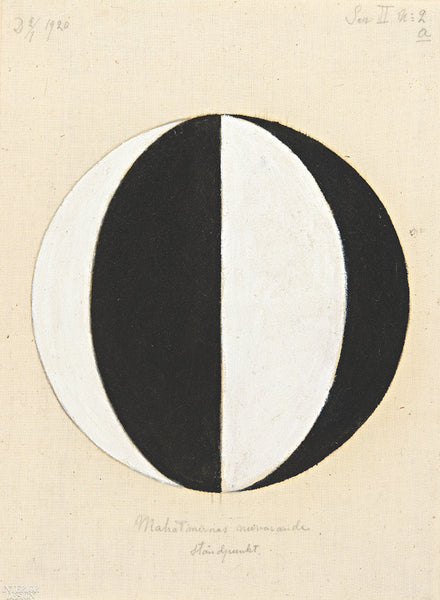

2) Science. There were many major scientific discoveries being made during Hilma’s time, such as subatomic particles (1897), electromagnetism, X-rays (1895), and radioactive decay (1898)- all of which overturned conventional world views. Hilma’s work was very informed by two scientific motifs especially, both of which were major themes in societal and scientific discussions at the time- that of evolution and the atom. The influence of the scientific world can also be seen in her work by her frequent use of diagrams.

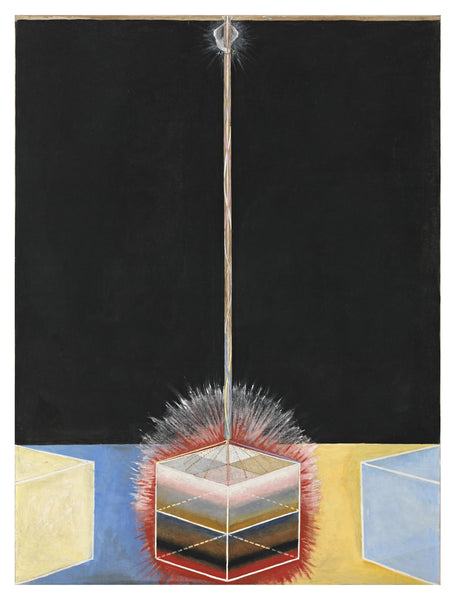

Series VIII. Picture of the Starting Point (1920)

Mahatmas Present Standing Point Series II, NO. 2A (1920)

Group IX/UW, The Dove, No. 12 (1915)

3) Swedish art. Hilma’s developmental years coincided with the revival of Swedish folk art. Her work shares similarities with the Swedish bonader, or painted wall hanging, which features flat, outsize motifs, a monumental scale, bright color, abstracted imagery, geometric shapes, patterns, flowers, and the incorporation of text. These hangings often portray the cycle of life, as Hilma does in her series The Ten Largest.

|

|

Image A: Group IX/UW, The dove, No 8 (1915)

Image B: Group IX/UW, The dove, No 8 (1915)

AESTHETIC

Hilma’s work can be characterized by the following:

|

- remarkable, vivid color combinations - matte colors - large scale, monumental formats - shapes that are at once both organic and otherworldly - floral and botanical motifs - ornate and decorative lines |

- organic forms which alternate with geometrical shapes - elaborate geometric lexicons- schematic drawings and diagrams - strong use of symbols to represent spiritual concepts - forms reminiscent of atoms, emissions or radiation |

Image A: Group X, No. 1, Altarpiece (1915)

Image B: Group X, No. 2, Altarpiece (1915)

Image C: Group X, No.3, Altarpiece (1915)

THEMES

Hilma was not concerned with abstraction for its own sake- her focus was finding visual expression for a spiritual reality beyond the observable world, which she called a “ primordial image.” To express this unseen reality, she produced symbols drawn from nature, religion, language, folk art, science and the occult. She used a mix of floral, geometric and biomorphic forms, as well as letters and invented words. Hilma’s notebooks contain keys to many of these symbols. The notion of evolution and the idea of earth and humanity as a microcosm for a larger reality also featured heavily in her work.

Some of Hilma’s common symbols and recurring motifs:

- Spiral. A common metaphor in theosophy, representing evolutionary development- a spiral winding counterclockwise was associated with the power of thought, and one winding clockwise associated with the power of emotion.

- Color. Hilma created a system of color - blue was associated with the feminine, and yellow as masculine; their unity is signified by green.

- Prisms. Represented ascending states of consciousness.

- Tree of knowledge. Common in biblical, mythological, and gnostic traditions.

- Pyramid. Stood for progression of knowledge, finally arriving at spiritual/mental plane.

- Flowers. Roses stood for masculinity; lilacs meant femininity.

- Swans. The swan was said to embody the “ mystery of mysteries,” the “ majesty of the spirit. ”

- Snail shell. Stood for the transcendence of oppositions, especially the duality of male and female.

- Scientific/biomorpic imagery.

- Letters. The letter “ u “ was used to signify the spiritual, ” w” physical matter.

|

|

Image A: Group VI, Evolution No. 15 (1908)

Image B: Group VI, Evolution No. 16 (1908)

Finally, Hilma is taking her rightful place in art history. In October 2018, her dream of showing her Paintings for the Temple in a spiral-shaped building came true when "Hilma Af Klint: Painting for the Future" opened at the Guggenheim in New York City. The exhibition became the most-visited exhibition in the museum’s 60-year history, drawing over 600,000 visitors, driving a 34% increase in membership, and selling more than 30,000 copies of the exhibition catalogue. Mystic and mother of abstract art, Hilma af Klint is being written back into the history books where she belongs.

Andrea Warren will be running a series of courses at Wallack's in 2020. If you're interested in finding out more information, check out our Classes & Events Calendar here.

Click Here for a direct link to Andrea's 8-week class on Women of Abstraction

All images and words are provided by Andrea Warren for Wallack's.