Sarah Lacy is a Canadian painter who has participated in solo and group exhibitions across the country, and has had her works featured in private collections in North America and Europe. In 2015 was a finalist for the Kingston Prize, and two short years later went on to win the Artist’s Magazine Annual Competition for the figure/portrait category. She has also received a Certificate of Excellence in the 2017 Portrait Society of America’s International Competition. Additionally, in June of 2016, she received a culture grant from the City of Ottawa and has since been producing a lengthy body of work.

In October 2015, she solely opened The Drawing Room Studio, Ottawa’s first long pose life drawing studio where she hosts monthly long pose life drawing sessions and teaches classical figure drawing and painting.

We asked our resident Interviewer, Yuli Sato, to catch up with Sarah. Here's what she had to say about contributing to Ottawa's art scene, conquering perfectionism, gaining inspiration from every body type (and more)!

Thanks for having me here for tea! Can you talk about how long you've been here, as well as what this space is used for?

I moved to Ottawa in 2014, less than a year after I'd finished studying in France [at Studio Escalier]. I was looking for an art community and I started going to life drawing groups in the city. I met great people, but the spaces just weren't what I was used to. I have no sense of scale, so I thought, "I'll just open a studio myself." So, this place started as just a life drawing studio. Previously, I was over in Hintonburg where I had a live-work space. It was a 1400 square foot apartment, advertised on Kijiji as: "Been empty for two years, would be pretty great if you were an artist and you wanted to set up your studio here." And I was like, “Okay ... hi!”

That sounds pretty perfect.

It was great, but it had limitations. I could only fit about seven people at a time so it was limited to how it could expand. During the first year, we just did long poses where we would hire a model for a whole weekend. Everyone would do a 12-hour drawing.

Whoa!

Yeah, but I was used to that because of where I studied. We would have 45-hour poses and draw six hours a day, five days a week. I knew I could not convince people to do that here, but I thought I could convince people to do a whole weekend. It took off way faster than I expected. After about a year, people were begging me to start teaching. So I started and it turned out I loved it.

These workshops with weekend poses...you were just facilitating?

Yeah, exactly. I thought if I could split the cost of a model with multiple people it would be perfect, since it’s about $300 for a weekend. I also felt I could start building a community. I don't do well when I'm isolated … Since I'm not from here, I needed to find a way to break in. For the first year, I ran the sittings twice a month every other weekend. In autumn 2016, I started teaching two classes a week and I've pretty much been teaching since then, with hardly any breaks … leg break aside. After a year of that, I realized that there was so much demand that classes were starting to fill in 15 minutes. I thought if I could expand somewhere bigger and fit 12 students that would change things. It would also change my profit margins. I was mentored by a lot of business savvy people, so I went to the bank with a three-year cash flow plan and they said, "You seem prepared. Here, have some money!"

From my own experience, that sounds like a unique background for an artist - to have a business-savvy sense. I just feel it's uncommon.

Yes, I haven't met many other artists who have that background. In school, I did well in science and math, and art was just what I loved. I had a lot of health issues then and it took me until 20 to graduate from high school, since I had to keep dropping out to try to recover. I knew that regular university wasn't going to be a thing for me, so I decided to start painting and start having shows, at like, 19 years old. I just said, screw it. I moved to PEI from St. Catherine's (Niagara region) ws there for a couple of years and started teaching myself. I taught myself web design … I have no sense of what is reasonable. I think that's the overarching theme in my life: I just get myself into things because I'm like, "That seems like something I could probably do."

That's amazing. It seems you've experienced a lot of success with that confidence.

It's not even confidence. I think it is naïveté [laughs].

You need a bit of that too when you're an artist!

I have a 100% track record for figuring it out. So, in PEI I started doing social media consulting and then I built the web design side of it. I didn't want to get a job at McDonald's and I couldn't do retail. It was just too hard on my body. You can design websites while in bed, so that gave me a lot of freedom to keep painting. PEI is also dirt cheap to live in, not to mention beautiful. We lived 30 seconds from the Harbor in this 1870s Victorian gingerbread and paid $700 a month, all-inclusive. It was huge. We had the entire ground floor.

Wow. And what was your reason for moving there?

Just on a whim. My partner at the time wanted to go to university there, and I had been there the summer before. I thought, why not. There were no opportunities where I was living, I love the sea and I liked a good adventure.

You don't have any post secondary schooling at all? You're self-taught?

I spent two and a half years in France. I have a lot of "post secondary" experience, but I just don't have a piece of paper. At 23, I found Studio Escalier, and thought, "This is what I'm looking for." I've always loved traditional, figurative, and realist work. I knew university wouldn't teach me those things.

Do you mean universities in Canada?

Anywhere. Well, China, maybe. Russia.

So, you didn't want to go to China or Russia?

[laughs] I didn't want to go where I did not speak the language at all. At least in France, I could speak French. The school is also run by Americans.

At Studio Escalier, did you have to apply with a portfolio? And how long was the program?

Yes, and the time varies. The school has short programs around 3 - 12 weeks, and in the summer and autumn, they have two longer programs, just under six months total. It's all figure drawing and painting - six hours a day, five days a week - that's all you do. I met other people there who were doing it like post secondary education. I talked to my teachers and said, I want to come back, this is what I want to do. So, I came back to PEI, sold all of my furniture, moved the stuff I cared about into my parents' basement and then went back for another year and a half.

Were you still working at the time?

Yes, I was also running my web design business 30 hours a week outside of class.

Wow, you must have had a lot of energy. You mentioned that you have always been into figurative and traditional technical drawing and painting ... Did that start in childhood?

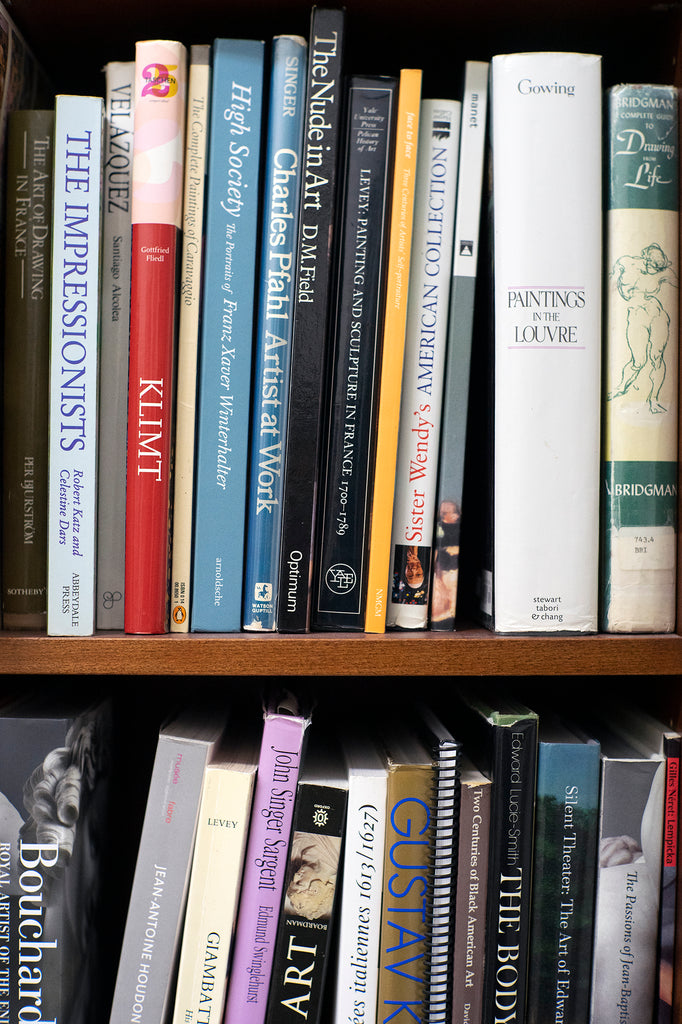

Yeah, my dad used to bring me art history books from the library. My dad was into art - not so much my mom, although she's an embroiderer. She's a seamstress and makes beautiful embroidery. She was interested in the arts but in a different sector.

That's still technical work.

Yes, highly technical work. My father was trained as a ship's draftsman.

Also technical!

Yes, he worked before there was AutoCAD, so you had to do the drawings by hand. Both of my parents are English. My dad was trained in Liverpool.

That's interesting.

Yeah. They're both technical people. I've always loved drawing and then once I got sick, I was housebound. Art was a thing I could still do and so I started looking at more art history books. I had a background as a dancer and have always been a physical person. Once I got sick ... you become ... your world turns into your own body. Your body becomes your story. I certainly could not have articulated that as a 16-year-old, but looking back, I think that's part of what drew me into art. And I've always loved portraits of people that I didn't know. I'd think to myself, "You've been dead for 500 years, but your face is still with us." That fascinated me. When I was 16, I saw my first Velázquez painting and thought..."That. I just want to make that. If I can do a quarter of that, I will die happy."

Can you describe your techniques in more detail?

I'm always building a 3D model of the subject in my imagination that I'm working from, as well as what I see in front of me. I'm also usually referencing a colour study that I make before every painting so I know what the average values and colours are for all of the major planes of the body and background. This allows me to work section by section rather than working up the whole painting at once because I can see the whole finished painting in my head. I paint the area of highest contrast first to "key" my painting and set the average lightest and darkest values. I then work out from there, bringing each section to about 75% completion. I tend to pick one section to work on per painting session (however long that is) and then soften the edges so I can easily knit the next section into it when I come back. Once the whole painting is worked to about 75% completion, then I go back through adding details and bringing each section to its final resolution - this usually looks like refining the drawing and adding my darkest darks and lightest lights.

Has your style evolved?

I've refined my voice over time. The more skilled I become, the more I can decide what I want to say and not say. Stylization becomes a choice instead of a default.

I've always thought that was important. I don't believe everyone needs to be technical to make great work, but I feel it can help when you at least understand the technicals, then you can choose to employ them or not, depending on whatever effect you're going for. I'm not a highly technical photographer, but I try my best to continue to learn how to at least do something properly, even if I don't enjoy it. I can then choose not to be technical [laughs]. Having that choice is important.

Yeah, I agree. And even ... I mean, I love lots of different kinds of work that look nothing like mine. I'm not one of those people who thinks, “You have to make work like me and if you don't make work like me, your work is stupid.” In the realist field, there can be this reverse snobbishness sometimes. But I also have experienced that snobbishness from more contemporary artists who ask me, why do you even make work like this?

Do you think that traditional work is still relevant?

Yes, I think it's still relevant.

But what challenges do you face with your work? How do you justify this style to people who ask you, “Why do you do this? Why don't you just take a photo?”

I mean, first of all, I think we have accepted that cameras tell the truth. And they don't.

I agree, they don't. Many people think photography is objective, but of course, it's not!

Most people who say, “Just take a photo” don't understand that your values might be flat. It's monocular instead of binocular, so you lose this 3D quality. There's distortion and the camera is not a substitute. The realist field is having a huge resurgence though, particularly in the States. It's starting to spread to Canada and Europe as well. In China it's huge, and in Russia, you're still seeing it because the academies are still going. The argument against it being pastiche is like, well, we've said everything that we could say. But, okay ... so a bunch of dead white dudes said a lot of things. But, I'm not a dead white dude. So can I maybe say some things before we decide this is dead? [laughs] Also, I have no interest in trying to revive things either. I'm not trying to make my work look like it's the 18th or 19th century. I think that we can take a lot of those ideas, concepts, and theories but still paint modern life. My figures are modern people.

When looking at your work, it was obvious to me that your figures are contemporary. The people you depict aren't who would be depicted in that traditional era. So even just for that reason, sure, you might be using a more traditional technique, but you're representing people who weren't represented previously.

Exactly. That is a huge part of my work. One of my criticisms of the genre is that sometimes the same models are used. Some are actual fashion models. We can say more interesting things than that … such as all bodies are good bodies and deserve to be art. All bodies have fascinating stories. That's what I love about figurative work. It's what I loved about my training because they weren't just interested in recreating the past. We talked a lot about what the shape of humanity is, and whether or not you can understand someone's body from the outside. It's important to have empathy and compassion and to not just see people as an assemblage of shapes, but an actual human being who you can come to understand some deep truths about. We all have a body and we all have all kinds of experiences. Our bodies don't ever forget.

Bodies also change over time.

Yes. I'm the person who's like, “Please don't get rid of your cellulite. I love your cellulite. All I want to do is draw your cellulite.” I had a model say, “I love the art that you make, but do you have to document every dimple?” And I said, “Yeah! I love your dimples!”

People often ask me, can you just Photoshop this and this when you take my photo?

I had the reverse rule. My wedding photographer was obsessed with Photoshop. I sat her down and said, I don't care if there is fat coming out of the top of my dress. You leave that there because I want to recognize myself 10 years from now. Things you can get rid of are the dark bags under my eyes and also the Band-Aids on my arm because I saved my cat that morning … He scratched me and I had to get a tetanus shot the day of my wedding. So yeah, you can Photoshop out the Band-Aid. But my body is fine the way it is, just leave it alone.

What relationship do you have with your models? Do you get to get to know them or does it depend on the person … how much do they reveal about their personality?

It depends on the person. I care about creating a safe environment here because I do hire models who are people of color, are different sizes, ages and have different backgrounds. I make it clear to my students that the model is number one, you don't touch her or him, you don't yell at them. We do not objectify them. They're a vital part of my learning environment as well as my work. A lot of them have become good friends and are a vital part of the community. They're important to me as both an employee and someone that I care about and feel protective of.

Do you consider it to be more of a collaboration? Do you get a lot more when someone is open as opposed to closed off?

Yes, I do. If a model is closed off, we tend not to work together again. I'm encouraging curiosity in my students. I want my model to be just as curious about what we're doing and why we're doing it, because then they come up with better poses, make suggestions and contributions. It makes the atmosphere much better for everyone.

Do your models talk when they sit?

Some are pretty chatty because they've learned that we're not drawing their face most of the time, we're talking about their body. I keep emphasizing to my students: it's life drawing, not corpse drawing. The model is going to move and you have to be flexible because if they shift a bit, you don’t want to be in tears on the ground ... there is a correlation between technicality and perfectionism.

Yes. I was going to say, most of your students are probably perfectionists.

Yeah, but also looking at the fundamentals: grace and movement are the first things we talk about because you cannot put that in later. You can't draw a stiff figure and think, now I will make it graceful. So, when we're talking about grace, we're talking about what are the shapes of organic form, what is the shape of humanity? They're wrestling with deep questions. It's hard.

Do you work with students' conceptually or is it just technical?

It's mainly technical. I'll talk more about concepts with students who are interested in a career as an artist, but I would say 75% of my classes are people who are serious but it's also just their hobby. They want to do it well but it's for themselves; they're not interested in being "artists." The remaining quarter has things to say and they want to be artists.

To bring it back to where we are now, in Ottawa: What brought you here originally? Just another whim decision?

When I came back from France with my partner, we were living in Cambridge, Ontario, which is not the most artistically inclined city, so I didn't enjoy it. We were deciding between Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal. Toronto was too expensive and I knew that I couldn't stay self-employed there. I speak French, but my partner at the time did not speak enough French to get the jobs that he was looking for in Montreal. So, we chose Ottawa. My best friend for 25 years also lives in Ottawa.

I empathize with that. I went to university in Montreal and tons of my friends live in Toronto. After I moved here everyone asked, “Why did you move to Ottawa of all places?” Some of my closest friends live here, so I also thought, it's a good place to land. We have a nice city. It might be quiet, but there are a lot of cool things happening here.

You have to find out the underground stuff, which I like. There also seemed to be a lot of life drawing here. Three weeks after arriving, I was out at art openings and forcing myself on people until they became my friend [laughs]. Ottawans are a little reserved, but if you just keep showing they eventually recognize you. There are also apparently the highest number of artists per capita in Ottawa.

We need to change the perspective of this city!

Also, every time I come home from Toronto I'm just like, “Oh my God, clean air.” I do love living here. We have lots of amazing models - way more than anybody expects. I'm always looking out for faces and scouting every person on the bus. I've got to keep my sunglasses on.

I run a book podcast with a friend and one of our segments is called Books Spotted - we always joke about how on the bus we're looking around people's shoulders like, “Hey, whatcha reading there?”

I'm that person who says, "Has anyone ever told you your mastoid process is beautiful?" [the bone at the back of your ear]. I will give you the strangest compliments. I notice the parts of people's bodies that no one else has ever slowed down to tell them is beautiful.

That must boost people's confidence.

That's the feedback. I find that the work I do does help some people who have struggled with self-confidence. They come in here and all I see about them are wonderful things. No one is criticizing your body here. Everyone thinks your body is amazing and they’re excited to paint it. How often are other people excited about what your body looks exactly the way it is?

Not often.

Right? It hardly happens […] In my studio there are a lot of emotions. My students struggle with things that I have struggled with. Perfectionism, 100%, has been the demon on my shoulder in the past. But it's about harnessing it and turning it into a tool. It's a sharp knife and you don't want to turn it on yourself.

That's a great phrase. I'm writing that one down.

I tell students: use that ambition to push yourself forward and make yourself amazing. But only turn the knife on the work. That's the biggest thing I got from studying at Escalier; it gave my inner critic. Instead of saying, “Wow, this sucks because I suck,” you say, “Wow, this isn't working because X isn't right.” You ask, “Why is this not working? What isn't happening here?” As an artist, you're a shark and you do not want to stop swimming. We don't need to demonize that yearning - we need to learn how to celebrate our wins.

Exactly. It's a balance. You need to remember you're doing a lot of good things. People always tell me that, because I always think that I'm never doing enough. But it's important to remember: I'm doing this, this and this and need to celebrate the wins.

I still struggle with that and I tell my students regularly. When we're students we cannot see our progress. My job as a teacher is to keep pushing you forward as well as to hold the arc of your entire progress. I can remind them that they have made huge leaps and bounds. I tell them to go home and pull out their old work. You want to see what you were doing 12 months ago because you are light years ahead of that now. And you're still light years ahead of where you want to be. Even in my practice, I don't feel happy with most of the things that I'm working on. I'm always yearning for new things, it never stops.

What are you working on right now? What is one thing you're striving for currently in your work?

There's a change in direction coming. At the end of the day, everything is still about the body. I've had a lot of experiences, both positive and negative ... I have been through enough therapy and now we can turn it into art. I'm looking for a different emotional impact. I'm going to explore darker topics that are more challenging for people, touching on abuse, trauma, and physical illness. I have a leg made of titanium now and I'm 6 - 12 months away from the muscle rebuilding because I snapped it in half. I have scars and my body is starting to show the signs of my life. I feel it's time to turn the lens back on myself, with the gift of time and perspective. There's that "10,000 hours to mastery" idea...

How many hours are you?

Probably 8,000 or 9,000. I might be closer to 10,000 than I think at this point because I don't always think about the amount of time like teaching.

As you've mentioned, you are a teacher. But who teaches you? Who mentors you?

I've been fortunate that my teachers have kept in touch. I'm also still their web designer. They can't get rid of me - I'm in there like a tick.

Do you send them images of your work and ask them what they think?

Sometimes. Tim is the one who mentors me more actively. Occasionally Michelle will just drive by with: "You made that ear too small!" She's such a beautiful painter. Whereas Tim, I love his draftsmanship. Tim and I also follow each other on social media, so he'll see works in progress.

He's probably zooming in on your Instagram and scrutinizing.

Completely. He'll come through and push me in new directions. Sometimes he'll send me images and say, “This could be an interesting thing that you should think about incorporating.”

Do you find social media and sharing your work online to be a positive experience or is it mixed?

It tends to be a positive experience. I've been fortunate that I don't tend to get a ton of trolls. What I do get is people who do not understand that just because it's nude, doesn't mean it's porn. I have had a few weird experiences ... been threatened. I have rules on the website for a reason.

I can only imagine. You must face a lot of challenges in that respect, especially being a woman who's taking ownership of depicting the body. A lot of people can't handle that, they just can't handle that confidence and they completely misinterpret it.

Yeah. When I started the life drawing group here, I was the only life drawing group run by a woman in the city. Isn't that bananas? Now there are two others, so it's better.

You're a trailblazer!

Accidentally. It didn't occur to me that it wasn't a thing someone would do. But yeah, why not? Oh, and you mentioned the term "draughtswoman" in your email - So the reason I say draughtswoman instead of illustrator is because “drawer” is a horrible word. Originally the term was draughtsman. Well, I'm not a man, so I’m a draughtswoman. This is different from illustrator because that is someone who would work in a more commercial aspect, whereas draftsperson or draughtswoman is a description of a skillset. It means you can use a pencil pretty well.

Before we finish, I'm going to ask a few rapid-fire questions. If you could paint any person past or present, who would you choose and why?

That is a tough one. My first answer is Misty Copeland. Her body is amazing, and she’s beautiful and poised. She's a trailblazer and is the first African American principal dancer for an American ballet company. Before I got sick, I was a classically trained ballet dancer until I was 12 years old. I got to the national ballet school and that was a thing I was going to do. I was like, should I be a dancer or a brain surgeon? I just love bodies and I like to see what's inside them [laughs]. And at one point I wanted to be a therapist as well and that's worked its way in.

I'm going to have to look into Misty Copeland. Moving on, in your opinion, when is an artwork successful?

When it hits the right note of being technically skilled, but the technicality is subverted to the emotional impact. Technicality is not there for the sake of being there; it's there because it says what I want to say in a better way.

How would you describe your work in three words?

That is challenging. Intimacy and grace are two of the words, and humanity is the other one. None of my pieces are huge because I want you to get up close and personal with the person in front of you.

How do you know when an artwork is finished?

When you stop having intelligent things left to say. I'm constantly saying to my students that your brain and your hand should always be moving together. There should never be any mindless strokes. Sometimes that means walking away for a week or a month and then coming back and saying, “Okay, do I still have nothing left to add?” If I still have nothing left to add, that's it. We varnish it, we sign it, we're done.

I have a friend who does technical work, and she was saying that she has a hard time saying "this is done." I wonder if certain people just can't stop?

You have to know what your end goal is. I struggle with finishing an artwork, too, but if I've hit that point and there's nothing left to do that will add more feeling to it, then I'm only adding more noise. There's no need for that. Also, some artists don’t want to sell their stuff and let it be out in the world. I've never struggled with that because I don't make the end product for me, it’s for the world to experience. The process … that's mine.

It sounds like you have a healthy approach. You start at zero and end at 100. You say, I'm satisfied with this and I'm not lingering. I'm not attached to it. I did everything I needed to do. That's a great attitude. Just let it go.

I can be ruthless in that way. I recycle stuff regularly and I think it’s important to purge. I'm not precious about things. I don't think every single thing I've ever made is amazing and I'm not a special snowflake. Some of it is garbage because I'm having an off day and I made a bad painting. That’s fine.

So, you're not a nostalgic person?

I'll get oddly sentimental about certain things, but when it comes to my work, I'm not sentimental... or maybe I'm sentimental with a purpose.

That's what it seems like. You're interested in hearing other people's stories and understanding their emotions. So, I mean, that's not sentimentality per se ... what I'm saying is you're not unemotional.

I'm interested in empathy, but I'm not interested in emotion without reason. I'm nostalgic about some of the paintings I made in France, though. I'm keeping those because they’re a memory I want to have. Whereas other pieces ... if I just keep them, then what was the point? […] I take my work seriously, but I do not take myself seriously at all. I make fun of myself constantly while I am teaching. I think it's important to not take yourself seriously because it's a lot harder to handle rejection.

I'm getting so much good advice here [laughs]. This is like a therapy session.

I try to say useful things. I like that question you asked via email as well, What advice would you give other artists? Stubbornness is the number one thing. Then commitment and perseverance. I'm also not very patient. People think that the work I do takes a lot of patience, but I'm just disciplined. You can train yourself to be this way. You can give yourself routines and say to yourself, I get to scroll Facebook for 15 minutes, but first I have to work on this painting for 45 minutes.

I would agree that discipline is very important in the artistic field. It's not the only difference between success and “failure" but sometimes things just take time and a whole lot of commitment.

Exactly. Also, if you quit you can't succeed. 95% of success is being the only person left standing in the room … Based on what I've read, a 10% success rate means you're doing great. That's based on other artists I've spoken to who are professional. Finding where you succeed matters too, and this is where I don't do as well in the Ottawa market. I struggle to find places that want to show my work here because I fall into this strange category of being both too passé because it's realistic, and also because it's naked people [laughs]. In terms of the one year I tracked everything, I think out of the 20 things I entered in Ottawa, I got into one. Then everything I entered in the USA I either got a first prize or an honorable mention out of thousands of entries.

Interesting.

It's important to pay attention to where you do well and throw your money there. But I am a big fan of the spaghetti wall method: just throw a bunch of spaghetti at the wall and see what sticks. You just have to keep trying for grants and competitions. You never know when you're going to be the exact person they were looking for.

For sure. Besides Velázquez, do you have any other favorite artists?

Frida Kahlo because her story resonates with me. I didn't have her bus injuries, but the pain condition she developed later - they think we would have had the same one. I could also relate to the way she used her body to tell a story. She painted so honestly and did not bullshit. Her portraits were never flattering; they're like a raw nerve ending. I also love Vermeer, for his quality of light, and Artemisia Gentileschi. Her work is bold and courageous. In my grade 12 art history class, I made a slide show showing how you can immediately spot work made by female artists. If you look at an overarching history of the female body, they're the ones where you think, “Oh, I know her, she lives down the street from me.” Whereas male artists tended to idealize. Their women never feel real, like a woman who walked in off the street. Artemisia Gentileschi’s paintings always feel like, “That's the fishwife from three doors down.” She is wielding that sword the same way she would chop off the head of a fish, right? I think that has influenced my work a lot, as well as seeing that raw honesty of the human body in a way that hasn't been idealized.

At the end of the day, all these stories, fables, myths are about actual people and we turn them into archetypes and monoliths. But what happens when you recognize that person? You can relate to that story in some way. It comes back to that personal quality and intimacy. It's not a collection of shapes up there. She is not a stand-in for every woman ever. It's a human being who will get up and go have a life outside of this painting. That makes her so much more interesting.

I think that's a great way to wrap up this interview! I think we tackled a lot.

Oh, I should add my favourite Wallack's products! Gamsol, because now we can paint with oils without dying. The art pro brushes I like - the green ones. Finally, Holbein paints. They're nice paints and a nice price point. I do like Gamblin, but Holbein is my favorite!

Perfect. It was wonderful to chat with you, and thank you so much for having me here, Sarah!

Check out Sarah's Website to see some of her recent work: http://smlacyart.com/

And her Instagram here: https://www.instagram.com/smlacy/

You can also see Yuli's instagram here: https://www.instagram.com/yulisato/

Interview and images have been provided by Yuli Sato for Wallack's.